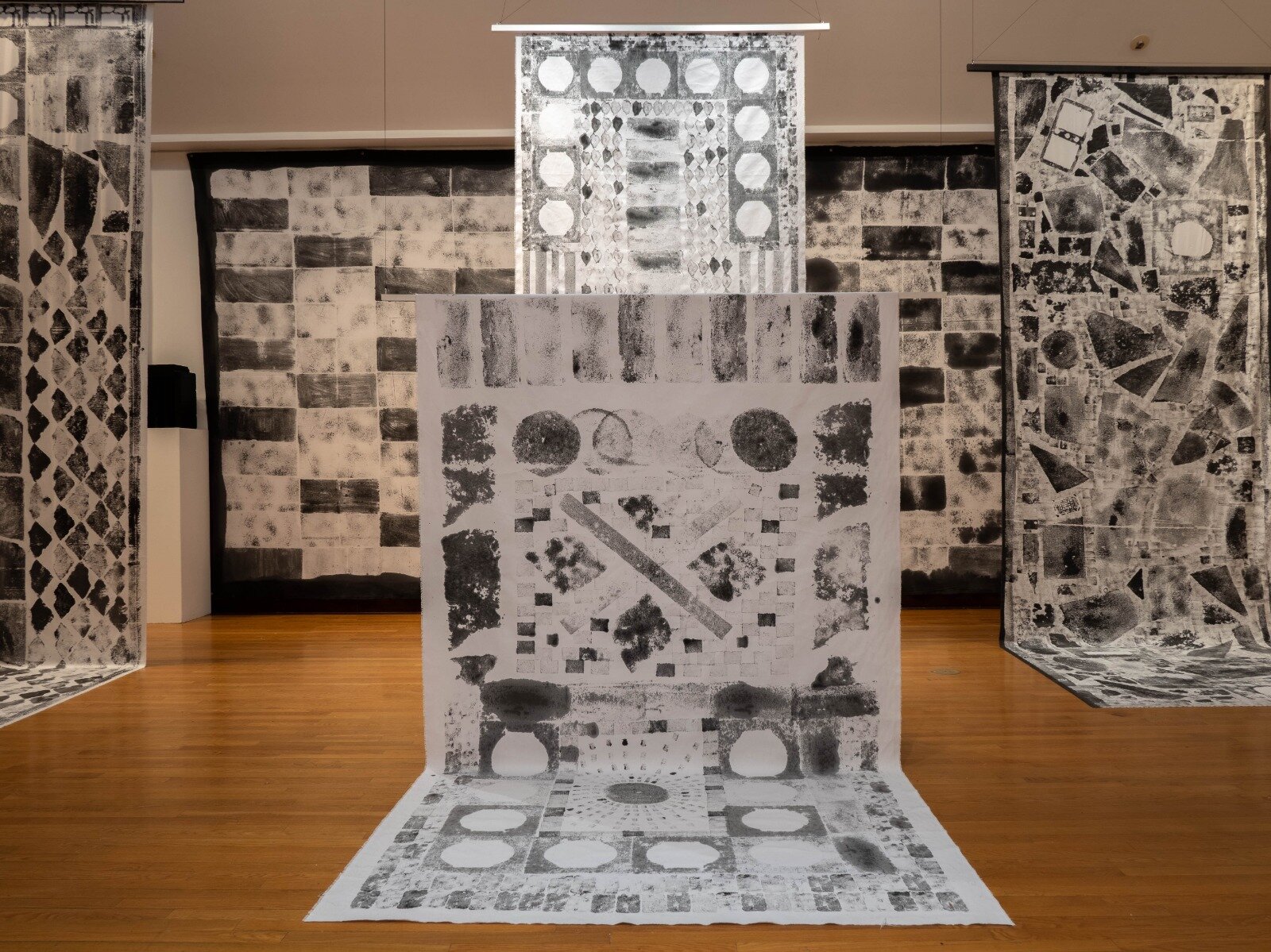

GOMITAKU : IMPRINTS OF THE HUMAN IMPRINT

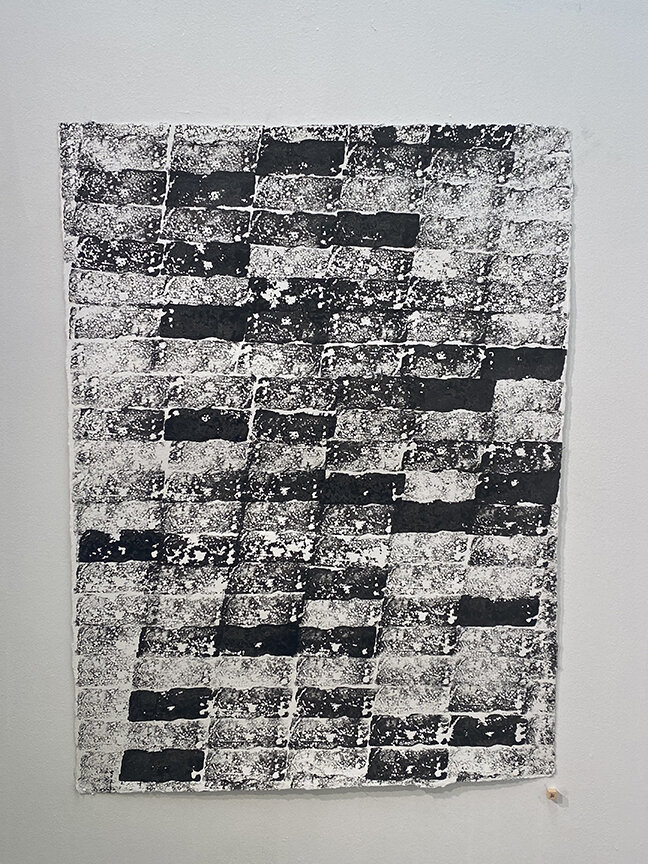

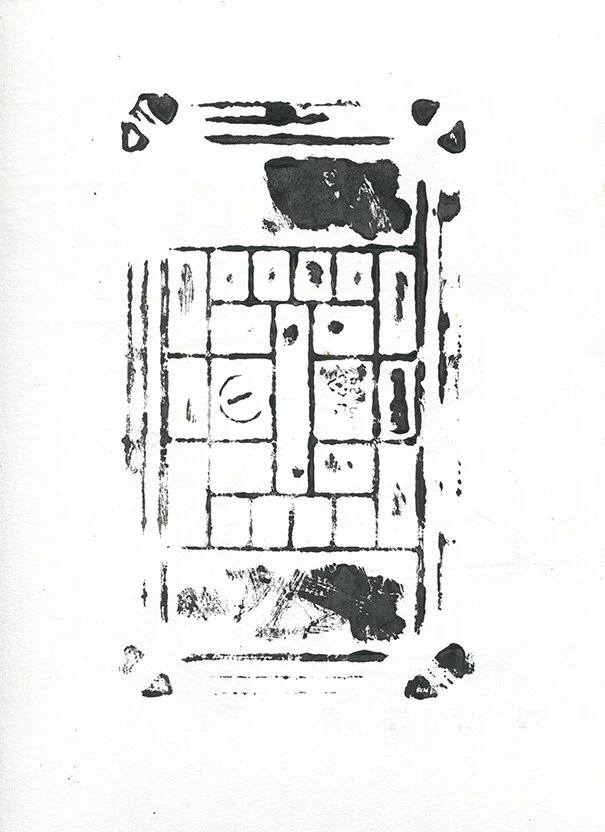

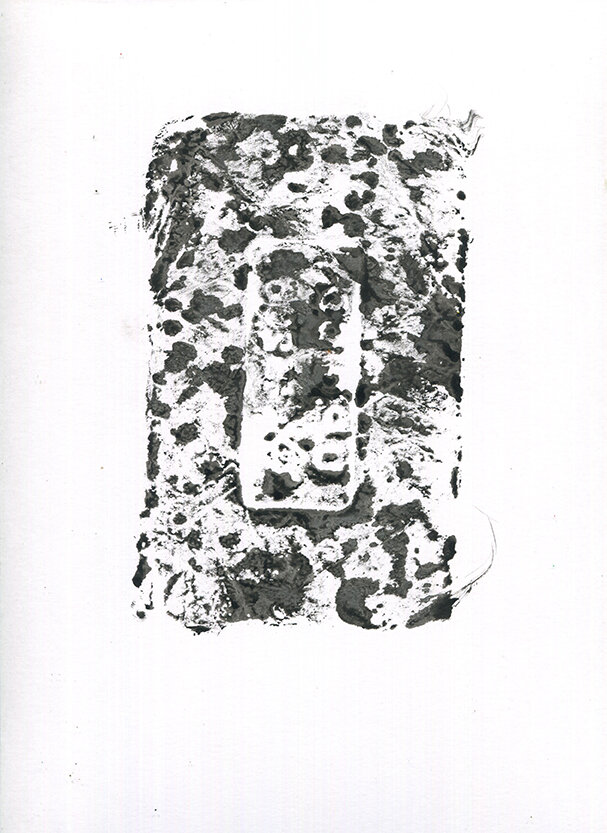

Gomitaku or “trash impression,” is my adaptation of the Japanese fish printmaking technique Gyotaku. Styrofoam and other detritus fished from waterways replaces the fish as a print material and acts as a visual language that engages in our detachment with water, waste and its interconnectivity to a multitude of injustices. The resulting mono prints conjure the dark shadow each object globally casts in unseen landscapes, their textured “scales” reflecting back at us the layered impressions of our environmental oppression. The often broken shapes are fragments of larger objects whose phantom pieces remind us of their possible futurity in the stomachs of fish and birds, nestled into folds of a shoreline, or added to the 51 trillion microplastic particles floating in the sea. The works also reference the watery habitats from which they were poached, hanging like waterfalls, floating in the air and sometimes existing in pools of printed matter on the floor that intersect with one another and go off on tangents like tributaries. The improvised patterning is akin to petrochemical petroglyphs that give visibility to the present that we currently ignore, the potential futurity of these objects that we are in denial of while also connecting us to their past, which we most often want to conveniently forget.

Printmaking in the Hydrocommons.

Tsunaminagashi is my adaption of the Japanese marbling technique suminagashi, or floating ink, that collaborates with water to create mono prints of moments in a water’s history. These prints are facsimilies of the human imprint on water’s body, directly mapping the embedded residue of abuse with oil, metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), petroleum products, and chlorinated solvents. Tsunaminagashi reimagines the hydrocommons as an art studio while capturing the pervasive but elusive effects of what is known as “slow violence.” These place-based collaborations reclaim unused spaces in the commons and liberate the confines of art making beyond the white cube.

TSUNAMINAGASHI and the Art of Water

Water came to me and my art practice in a natural way. I’ve always loved printmaking - the process, the ritual, the repetition, and the multiple reproductions - but it wasn’t until I discovered suminagashi, that I felt like it was my calling. I began experimenting with the ancient Japanese tradition of suminagashi, or floating ink, around 2012. I had started painting big abstract paintings with the luscious black calligraphy ink known as sumi after visiting Japan and nerding out on handpainted signs there. I was in love with the urgency of the brush stroke, the immediacy of the intent and the seemingly neverending line - one dip of the brush and you were good for a long while. One day I spilled some sumi ink in my water cup by accident and realized that the ink stayed on the surface of water. When I stuck a little piece of paper in there, I pulled out a black and white marbled print. It was magic. I did it again. And again. And again. I thought I had truly discovered something new but after a little research, I realized it originated in the 12th century and it was called suminagashi, or “floating ink.” Lol. I was just a little late to the party! But not a problem.

It was practiced as a form of divination by Shinto monks in addition to their calligraphy on scrolls. The natural black sumi ink was derived from the soot of pine trees found in the countryside of Japan. Suminagashi however, involves making a floating painting on water, then laying the paper on its surface, and capturing a monoprint of that moment in time. Within the animistic religion of Shinto, this act forms a bond between the artist and water with an opportunity to gain knowledge from her spirit. To be successful at suminagashi requires treating water as an equal, living being. The Shinto monks’ rejection of anthropocentrism is embodied in their relationship to water and I immediately felt a kinship to this way of thinking and being.

It is a collaboration with water—you cannot control it and make it do exactly what you want. Instead, you work with it and allow each of your brush strokes to be taken over, spiraling into the water’s currents, guiding the floating ink infinitely, patterning, pooling, settling. I have let paintings float for days, thrown leaves and dirt in the water, collected rain water, river water, and encased the water in sealed containers -all of which have their effects. Suminagashi has aided in my own unlearning of anthropocentrism; I have given up total control and instead, happily allow her to choreograph my movements. What will happen? It has since become quite the love affair. I’ve introduced colors, worked in oil drums, buckets, bowls, and inflatable swimming pools. Water was now the subject of my work as well as the medium, the canvas, and the compass, helping me navigate from one project to the next.

Water as a site and medium for art making can be a challenging endeavor. She is unpredictable, formless, and always moving but it is these very properties that I have come to celebrate. Living in New York City for the past 20 years, the waterways here surround us and yet for many, they are virtually unseen. Hiding behind the facades of skyscrapers or factories, it can be easy to forget we are on an island. As the spectacle of commerce and glitz adds to further the distraction, there are some of us who have taken advantage of their overlooked potential. When I first moved to Greenpoint in the early aughts, I spent many a day and night on the abandoned waterfront. The condos had not descended upon the water’s edge just yet. Instead, there were weeds growing 8 feet high and fences one could easily slip through. Once on the otherside, there was freedom – and the best view of Manhattan.

The waterfronts along Northern Brooklyn had become peoples’ parks—neglected by the city and rightly taken over by the kids. Trucks and cars were turned over or had been set alight. Marching bands practiced, flaming soccer matches played, and I set up shop often reading, drawing, or sewing the wristbands that I sold on Bedford Ave. It was the scene of many a mob hit back in the day but we ate it up, drinking wine into the wee hours perched in old fishing chairs that used to be attached to the broken piers, legs dangling over the dark waters of the East River. This was a secret amongst a certain group of adventurers for as long as it could be one—NYC is a damn hard place to keep a secret. Especially, when the Mayor blows up the spot. As a residential rezoning happened in this industrial zone under Mayor Gloomberg, warehouses that held artists would be evicted, gutted, knocked down or repurposed for fancy multimilllion dollar luxury loft apartments. The jig was up.

Alas, we just kept it moving, following the water’s edge and soon I found myself along the banks of the Newtown Creek. The Creek is more of a canal and was the closest body of water to my apartment (still is.) A three and a half mile tributary of the East River that also happens to be a Superfund site and one of the most polluted bodies of water in the United States. The sordid history here reads like another dark tale in the war waged by capitalism over nature. Despite over one hundred years of toxic abuse, the Creek has its charm—and its smell. Good thing was that no one seemed to go over there and you could really get away from it all if you knew the right paths to get to it in between the factories that make up most of the shoreline. These secret spots of solace amidst the chaotic hustle of city life has certainly helped keep me sane. As I worked on suminagashi prints in my studio, I began to spend more time on the Creek and eventually had a eureka moment: I had been overlooking the presence of my collaborator in the large bodies of water that surrounded me.

After going on the water in a rowboat with water artist Marie Lorenz, I was hooked. She showed me how relatively easy it was to launch - and most importanly, how it was our right to do so. I got myself a 14ft jon boat not long after that and armed with scrolls of paper and chemical gloves, I began to explore the further depths of the Creek and make prints in her, with her, using her visibly very polluted surfaces, in a process that I have come to call “Tsunaminagashi.” Tsunami being a lot of something and nagashi, meaning floating. The art of Tsunaminagashi then replaces sumi ink with the tsunami of floating detritus prevalent after rain storms in the Creek due to the 22 combined sewage overflow drains that emit untreated wastewater directly into the tributary, stirring up the sediment into quite a cocktail of toxins. I slowly drift into these islands of waste and wait for compositionally exciting moments to emerge, often egging them on with an extended paint brush before laying my prepared paper down on her surface.

These ghostly prints are facsimilies of the human imprint on water’s body, mapping an embedded residue of abuse with oil, metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), petroleum products, and chlorinated solvents. Tsunaminagashi reimagines the hydrocommons as an art studio while capturing the pervasive but elusive effects of what is known as “slow violence.” The concept of slow violence is a gradual but devastating invisible threat that can be perfectly embodied by the Newtown Creek’s lingering 30 million gallon oil spill leaked by Exxon / Mobil over the span of decades. These monoprints incriminate the polluters, literally giving visibility to their dirty fingerprints while simultaneously celebrating the power of water to turn an oil spill into a thing of marbled beauty. Water has in turn liberated me from the financial constraints and spatial limitations of an artist studio, knocking down the four walls of the white cube and turning them into bridges that have led me to the water’s edge.

I cannot underestimate the liberation I felt being free of these confines. The idea of renting overpriced cubes to just sit in and make work for the rest of life began to feel like death. Water opened the world for me in a way that I hadn’t thought of before for some reason. Now, don’t get me wrong - I still work indoors and often - because I enjoy and need that solitude too. But working on, in and with the water, has enabled me to begin to think of more collective actions, of natural collaborations, of reclaiming unused spaces in the commons. To create mindful walks and discover the nature and wildlife that secretly exists in watery urban areas. This can be art too. This can be radical and civic, it can be meaningful and really simple.

I see a good many of us now, leaning in towards social engagements with abused landscapes, with all kinds of people in neglected neighborhoods, and its great. Art need not just be pretty things for pretty people. I like the challenge of working with something ugly. I always have. I’ll pick the shirt with a stain before a perfectly clean one - hell I’ll add a few more stains so its not lonely. Seeing and sharing that strange beauty in the ignored and mundane is a gesture for the world. For if we can acknowledge a battered waterway, perhaps we can acknowledge the reasons why we continually hurt our kin.